Alas, Poor Laurence...

People have told me that I quote Shakespeare too much. I never thought that was a flaw but today, when 'text' and 'friend' are now verbs, I can see their point. I do not consider myself an intellectual, which is why I am always puzzled as to why these same people insist that Shakespeare is too grand for the everyday man. I find it pretty easy to follow what the characters are saying.

It is in English, after all.

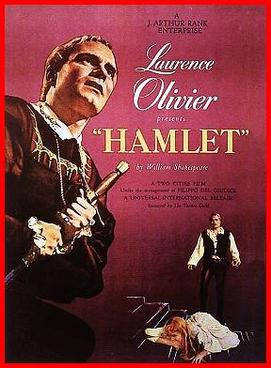

A great proponent of The Bard was Sir Laurence Olivier, and in Hamlet, Olivier uses all his skills as both actor and director to create a moody, atmospheric version befitting the Melancholy Dane. His film version of the play has faced intense criticism for cutting a great deal of the text (more on that later). The final product itself serves as a fascinating introduction to both one of the great works of the stage as well as one of the greatest interpretations of the title character on film.

People have told me that I quote Shakespeare too much. I never thought that was a flaw but today, when 'text' and 'friend' are now verbs, I can see their point. I do not consider myself an intellectual, which is why I am always puzzled as to why these same people insist that Shakespeare is too grand for the everyday man. I find it pretty easy to follow what the characters are saying.

It is in English, after all.

A great proponent of The Bard was Sir Laurence Olivier, and in Hamlet, Olivier uses all his skills as both actor and director to create a moody, atmospheric version befitting the Melancholy Dane. His film version of the play has faced intense criticism for cutting a great deal of the text (more on that later). The final product itself serves as a fascinating introduction to both one of the great works of the stage as well as one of the greatest interpretations of the title character on film.

On the off-chance that you don't know the plot, it involves the Royal House of Denmark. King Hamlet has died, and his brother Claudius (Basil Sydney) has married the widow, Queen Gertrude (Eileen Herlie) within a month of her husband's death. The Court rejoices, except for Prince Hamlet (Olivier), who is displeased that his mother appears to have forsaken his father and The Prince While he broods, guards have seen a ghostly figure walking the castle at night. They persuade Hamlet's friend Horatio (Norman Wooland) to have Hamlet speak to the specter.

Hamlet discovers it is the Ghost of Hamlet Senior, who tells him Claudius murdered him and asks his son to avenge him. Hamlet begins his plot of vengeance by feigning insanity, even if that means pushing his naive love Ophelia (Jean Simmons) aside brutally. After Hamlet has a traveling acting troupe reenact the Old King's murder in front of Court, Claudius has Hamlet exiled to England, but a twist of fate brings him back. However, Hamlet's brutality of Ophelia along with his accidentally killing her father Polonius (Felix Aylmer) has driven her mad. Her brother Laertes (Terence Morgan) seeks revenge, and as the saying goes, 'everyone dies in Shakespeare' (technically, this isn't true, but in this case, we do end with a lot of bodies).

Hamlet discovers it is the Ghost of Hamlet Senior, who tells him Claudius murdered him and asks his son to avenge him. Hamlet begins his plot of vengeance by feigning insanity, even if that means pushing his naive love Ophelia (Jean Simmons) aside brutally. After Hamlet has a traveling acting troupe reenact the Old King's murder in front of Court, Claudius has Hamlet exiled to England, but a twist of fate brings him back. However, Hamlet's brutality of Ophelia along with his accidentally killing her father Polonius (Felix Aylmer) has driven her mad. Her brother Laertes (Terence Morgan) seeks revenge, and as the saying goes, 'everyone dies in Shakespeare' (technically, this isn't true, but in this case, we do end with a lot of bodies).

Olivier opens up Hamlet to the possibilities of film with his brilliant camera work and Desmond Dickinson's cinematography. Olivier doesn't speak many of his monologues openly (including the famous To Be Or Not To Be soliloquy) but relies on voiceovers, as if we are allowed entry into Hamlet's mind. It brings a reality to those scenes because this is how we are when we have thoughts floating in our minds.

Olivier doesn't limit this technique to his own scenes. When Hamlet comes to visit Ophelia after having seen The Ghost, she narrates the scene as we watch, and both Simmons' vocal performance and her and Olivier's visual acting makes the scene fascinating rather than repetitive. Whenever The Ghost is felt we hear a slowly beating heart and the camera moves slowly closer and closer, each movement matching the heart's beat. When we finally see The Ghost, it is a figure straight from a nightmare: the shadows and fog creating an otherworldly feeling to Hamlet.

Olivier doesn't limit this technique to his own scenes. When Hamlet comes to visit Ophelia after having seen The Ghost, she narrates the scene as we watch, and both Simmons' vocal performance and her and Olivier's visual acting makes the scene fascinating rather than repetitive. Whenever The Ghost is felt we hear a slowly beating heart and the camera moves slowly closer and closer, each movement matching the heart's beat. When we finally see The Ghost, it is a figure straight from a nightmare: the shadows and fog creating an otherworldly feeling to Hamlet.

The shadows, the fogs, the panning shots up and down staircases creates a very German Expressionist style to Hamlet, a dark, oppressive world that is slightly off-kilter, somewhere between barbarism and civilization. It never felt stage-bound but it was never realistic-looking either, and this is the brilliance of Hamlet. Olivier visually takes great advantage of the vastness of the sets, even using the empty spaces to great visual advantage, as when the Acting Troupe arrives seemingly out of nowhere with only joyful music to announce their arrival.

A more haunting moment is when Ophelia finally succumbs to her insanity. We do not see her suicide but Gertrude in a voiceover tells us what happened. We do see her floating in the river, and the soft delivery of Herlie's monologue mixed with William Walton's score creates a tragic, mournful mood befitting the emotional destruction of a gentle soul, a true victim of the evil men do.

A more haunting moment is when Ophelia finally succumbs to her insanity. We do not see her suicide but Gertrude in a voiceover tells us what happened. We do see her floating in the river, and the soft delivery of Herlie's monologue mixed with William Walton's score creates a tragic, mournful mood befitting the emotional destruction of a gentle soul, a true victim of the evil men do.

Olivier as director not only creates great imagery but also leads his cast to remarkable and beautiful performances. Aylmer's Polonious is a delight as a comic figure, foolish in his perceived wisdom. The same can be said for an early appearance of Peter Cushing as the foppish Osric, who creates the few comic relief moments.

In his one scene as the Gravedigger, Stanley Holloway has a rustic wit to match Olivier's Mad Prince. The Players of the Play Within The Play (including future Doctor Who Patrick Troughton as the Player King) create performances in basically a silent play (with only Walton's score to serve as guide), yet while we miss one of my favorite lines from the play (when Getrude says that the Player Queen 'doth protest too much'), we really don't miss it since Olivier trusts the audience to keep up with the plot.

In his one scene as the Gravedigger, Stanley Holloway has a rustic wit to match Olivier's Mad Prince. The Players of the Play Within The Play (including future Doctor Who Patrick Troughton as the Player King) create performances in basically a silent play (with only Walton's score to serve as guide), yet while we miss one of my favorite lines from the play (when Getrude says that the Player Queen 'doth protest too much'), we really don't miss it since Olivier trusts the audience to keep up with the plot.

The women have the best performances apart from the title role. Herlie's Gertrude is a remarkably loving and gentle woman, frightened for her son yet unaware of much of what is going on. She is both regal and motherly in Hamlet.

However, it is Simmons' Ophelia that is the hallmark of the film. She brings the gentleness and innocence when we first see her, but when she becomes confused, then terrified, then heartbroken at Hamlet's rejection of her in the brutal Get Thee To A Nunnery scene, we see how both her spirit and mind become completely broken. When we see her for the last time, her wandering about the palace to the horrified sight of the King, the Queen, and her brother is that of a living ghost, totally within her own world yet realizing that she has gone mad.

Simmons' performance is simply brilliant and will be the benchmark for any actress who dares tackle on the role.

However, it is Simmons' Ophelia that is the hallmark of the film. She brings the gentleness and innocence when we first see her, but when she becomes confused, then terrified, then heartbroken at Hamlet's rejection of her in the brutal Get Thee To A Nunnery scene, we see how both her spirit and mind become completely broken. When we see her for the last time, her wandering about the palace to the horrified sight of the King, the Queen, and her brother is that of a living ghost, totally within her own world yet realizing that she has gone mad.

Simmons' performance is simply brilliant and will be the benchmark for any actress who dares tackle on the role.

Olivier was forty at the time he played a teenager, but his performance has a vitality and a fury along with his constant indecision and wavering. Herlie was twenty-eight when she played his mother, and the twelve year age difference, while noticeable, doesn't impeded their scenes together. Olivier does create an Oedipal overtone in Hamlet, especially when they are in her bedchamber, creating an almost frenzied thwarted love scene. Earlier, when Gertrude leaves Hamlet, she and her son kiss on the lips for a rather long time, making the scene strange and uncomfortable.

As the center of the film, Olivier creates a man who truly cannot make up his mind, who is never sure when to take action or when to think things out. When we 'read' his mind in the To Be Or Not To Be soliloquy, his performance and direction give one the impression that somehow Hamlet himself is hovering between the worlds of the living and the dead, as if the fog is both within his mind and in the open air where his thoughts run. When he speaks as The Ghost, the soft, hushed, slow delivery makes the Ghost even more a frightful specter to the audience.

As the center of the film, Olivier creates a man who truly cannot make up his mind, who is never sure when to take action or when to think things out. When we 'read' his mind in the To Be Or Not To Be soliloquy, his performance and direction give one the impression that somehow Hamlet himself is hovering between the worlds of the living and the dead, as if the fog is both within his mind and in the open air where his thoughts run. When he speaks as The Ghost, the soft, hushed, slow delivery makes the Ghost even more a frightful specter to the audience.

Now, on to the controversy. Olivier's Hamlet cut approximately two hours of the four hour play, and some of the most famous characters were completely absent, most noticeably Rosencrantz & Guildenstern. This is how I will answer that criticism: frankly, I didn't even notice their absence. It may not be a faithful, to the letter adaption of Shakespeare's play, but Olivier did instead create a brilliant psychological portrait of a confused 'young' man.

It seems a silly argument to suggest that Olivier, one of the greatest Shakespearean actors and proponents, would create something that would somehow diminish one of the great plays.

Ultimately, Hamlet creates an intense story of revenge and loss, and if one would prefer a more literal interpretation, there are other adaptations readily available. However, the performances and the magnificent imagery within Hamlet lift this version to being one of the greatest in cinema. Hamlet should not be criticized for not being a direct adaptation, but should be embraced as a great primer to Shakespeare, giving audiences both an appreciation for great acting and brilliant storytelling.

It seems a silly argument to suggest that Olivier, one of the greatest Shakespearean actors and proponents, would create something that would somehow diminish one of the great plays.

Ultimately, Hamlet creates an intense story of revenge and loss, and if one would prefer a more literal interpretation, there are other adaptations readily available. However, the performances and the magnificent imagery within Hamlet lift this version to being one of the greatest in cinema. Hamlet should not be criticized for not being a direct adaptation, but should be embraced as a great primer to Shakespeare, giving audiences both an appreciation for great acting and brilliant storytelling.

Hamlet is not quite a filmed version of the play, yet not quite a play itself; rather, it's a conscious mix of two styles that work brilliantly. I won't argue that 'the play's the thing', but Hamlet is the film that makes the play work as film.

For more reviews of Best Picture Oscar winners, please visit the Best Picture Winners Retrospective.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Views are always welcome, but I would ask that no vulgarity be used. Any posts that contain foul language or are bigoted in any way will not be posted.

Thank you.