|

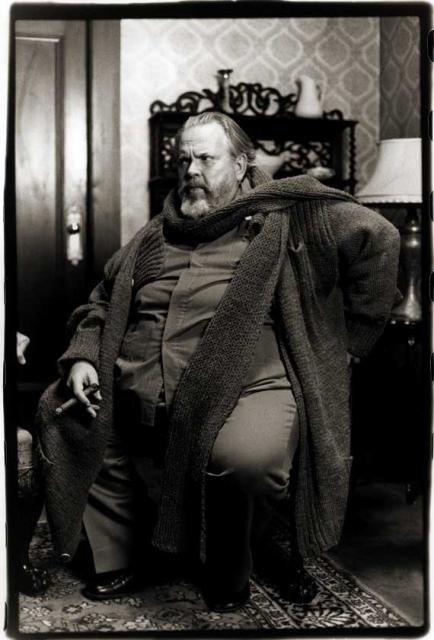

| 1915-1985 |

ORSON WELLES

To my mind, when I think of Welles I think of Icarus. He flew too close to the sun and ended up crashing into the sea. Welles reached the greatest heights, but then he fell, slowly, steadily, due to circumstances both exterior and interior, only to crash as a punchline and a man of many guest shots.

In retrospect, I wonder if Welles ever thought that perhaps making 'the greatest film ever made' meant that every other film he would make could ever match it, let alone top it. According to Peter Bogdanovich, theater impresario Billy Rose told Welles to quit films. "You'll never top it," he was warned.

Icarus takes flight.

Welles fought long and hard to get Citizen Kane released despite the smear campaign by the inspiration for Charles Foster Kane: William Randolph Hearst. He had put so much into it: his directing, his acting, his writing (along with Herman Mankiewicz), that to see it brought down would not have just been intellectually immoral, but would probably have wounded Welles on a personal level. However, I digress to wonder what would have happened if Welles had tackled The Magnificent Ambersons first.

Certainly Hearst wouldn't have bothered with Orson Welles as a person or artist. RKO would not have disemboweled the film (he did have full artistic control in his contract, a rarity in Hollywood). It might have ended up the way Welles would have wanted it to have been seen, not the way the studio thought it should have been. It might have all been different in terms of his career (i.e. allowed him to have a more productive one).

Instead, there was an arrogance to Welles, that he thought he could take on one of the most powerful men in the world and strip him bare for all the world to see. Hearst could have tolerated this upstart making fun of him and showing him to be a bitter old man, but by mocking his mistress Marion Davies (in the character of talentless shrewish drunk Susan Alexander) and worse, by throwing Hearst's alleged pet name for her special part (Rosebud) all over the film, it was waving a red flag in front of a bull.

Icarus comes too close to the sun.

While Welles survived the campaign against him by Hearst, the cost was exceptionally high. The power Hearst had over a frightened and cowered Hollywood cost Citizen Kane all the awards it deserved: certainly Best Picture, Bernard Herrmann for his memorable score*, and Gregg Toland for his innovative cinematography went without an Oscar because the Academy members were taking out their anger about all the problems Citizen Kane had caused them on the nominees. In fact, out of nine nominations it received only one Oscar: Best Original Screenplay (and according to the documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane, that Oscar was more for Mankiewicz than for Citizen Kane itself).

Kane had proved such a headache for RKO that for Welles' next film, The Magnificent Ambersons, they weren't about to let him run wild again. Thus, when he left for South America to film the documentary It's All True, the bigwigs saw The Magnificent Ambersons and decided to 'improve' it (or make it more to their idea of a movie). It should be mentioned that Welles left for South American BEFORE finishing editing The Magnificent Ambersons, and thus, giving RKO the entry it needed. In the end, the final film, while still extremely impressive, was not what Welles imagined. To add insult to injury, It's All True was left incomplete, and some of the footage Welles shot (including color footage of Rio de Janiero's Carnaval) was eventually dumped into the Pacific Ocean.

Now with The Magnificent Ambersons in all but ruins (or at least not to Welles' standards), we see that through a series of bad timing and bad decisions (from both executives and Welles himself), we watch the promise that was Orson Welles slowly fade.

The wax begins to melt and Icarus' wings slowly disintegrate.

Welles could make a film that fit the standards of the time. Take The Stranger, for example. Here, he was under strict orders to make a film on time, on budget, and to not deviate from the script. The result: a box office hit with critical acclaim. However, Welles soon started chasing his own ideas, pushing the medium that he described as "a very expensive paint box". His films became visually revolutionary and stunning but perplexing if one went by the actual plot.

Two good examples of this are The Lady From Shanghai and Touch of Evil. Both those films have some extraordinary visuals: in the former, the funhouse closing scene where a chaotic shootout ensues, and in the latter, an amazing opening sequence done in one continuous take. However, few people can say they actually understand what is going on. One gets the sense that Welles was more interested in what he could do with the camera than what the story was actually about. I figure if he were here, he'd give me a good argument that he did care about the story, but both films are at times confusing.

By failing with The Lady From Shanghai, Welles now effectively went into exile. It was one thing to be a genius, but it was another to be a genius that kept failing financially. He did manage to film MacBeth for Republic Studios (best known for making B-Westerns), but perhaps in hindsight having the characters speak with Scottish accents doomed the project. Even now, most Americans don't like hearing such broad accents in their films, but in post-WWII America it would have been almost laughable. In Europe, he made Othello (although because no one wanted to finance his films, he took two years to actually film it because he had to work as an actor to get the finances to put it all together). It was beloved in Europe, but not in his homeland.

However, there appeared to be hope for Welles. He was given one last chance at redemption, or rather a final opportunity to show he could make a good American film that could make money. That would be Touch of Evil. In retrospect, having Charlton Heston as a Mexican is perhaps one of the worst casting choices in all film history (side note: as a Mexican-American, I have always thought that Heston's make-up was far too exaggerated to be anywhere close to realistic to where it borders on blackface), but to his credit Heston talked Universal Studios into letting Welles direct.

Touch of Evil is a brilliant film, especially a tour de force opening that as envisioned by Welles is audacious and sheer genius, but the released version was a disaster financially and yes, a perplexing plot. Heston himself went on to call it 'the greatest B-picture ever made'. The failure of Touch of Evil is not Welles' fault: again, the studio took it out of his hands and decided to 'improve' it. However, by then, it was simply too late. Orson Welles as a director in American was finished.

Icarus descends into the waters.

How it all came to end for Welles from the brilliance of Citizen Kane to ending up selling Paul Masson wine (my friend Fidel Gomez, Jr. did a dead-on impression of the line, "We will sell no wine...before its time") is tragic. Part of it was that Welles was truly ten-to-twenty years ahead of his time. He clearly loved film and knew the potential to make true art out of cinema. As a result of taking chances, the money men feared they would not get a return on their investment and always meddled to get it more in tune with their ideas of popular tastes.

However, part of Orson Welles' fall was the fault of Orson Welles. His stubbornness, his ego, his inability to see himself as wrong alienated people who could have helped him. He was a genius, but a genius who at times did not play well with others. I look on the example of Don Quixote. I never understood why Welles didn't simply write an actual script. By filming things without setting them down, it only led to confusion and disorganization. In short, Don Quixote doesn't make any sense, and while there are beautiful moments the final product is not a good film.

It also didn't help that he became an object of ridicule. His weight became a punch line, and to a whole generation of viewers, he was just a fat man who performed magic tricks on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Orson Welles' brilliance as a director is up there, on the screen. Citizen Kane alone is enough to enshrine him in the pantheon of the greats. Mercifully for us, he managed to create more extraordinary films: The Lady From Shanghai, The Magnificent Ambersons, Touch of Evil, F For Fake, Chimes at Midnight. I confess to also enjoying The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (yes, he didn't direct this film, but since it was the first film with Orson Welles that I saw, not counting his cameo in The Muppet Movie, it holds a special place in my heart).

He has the added benefit of being a first-rate actor: going from Citizen Kane through small parts in such films as A Man For All Seasons and especially The Third Man. His voice is one of the greatest (even if you do end up thinking of The Brain from Pinky & The Brain).

In the final analysis, Orson Welles is one of the great directors not because he made the greatest film ever made, but because he made so many good films despite so many great obstacles. He might still surprise us even after his death: The Other Side of the Wind may yet be completed and released, so we might see one more Film by Orson Welles.

He created some extraordinary images on film, and paid a heavy price for it. He commented that he had wasted too much time on things unrelated to actually making a film. "It's been 2% movie-making and 98% hustling", he said about the difficulties of financing his projects (some alas, never to be completed). Still, what we do have of his work is a great legacy, one which all future filmmakers would be wise to study, appreciate, and draw from.

Orson, where did it all go wrong?

*Herrmann did win an Oscar for his score for The Devil & Daniel Webster which was nominated the same year. It is impossible to say whether this was an award for both The Devil & Daniel Webster and Citizen Kane, but one can wonder...

To learn more and to see the full Great Directors Retrospectives, click on the link.

To learn more and to see the full Great Directors Retrospectives, click on the link.

I would like to quote from this blog. Can i ascribe it to Rick Aragon?

ReplyDeleteThanks

Kevin

cinemahistory.com

You have my permission, and you can ascribe it to Rick Aragon. Thank you so much for asking and best of luck in all your future endeavors.

ReplyDelete